When scans make things worse: the unintended harms of spinal imaging - Part 1 System use and outcomes

Tanya Cambey & Dr Mary Wyatt

This article is the first of two on spinal imaging. Here we focus on the evidence that routine scans often cause harm without improving recovery. The companion Part 2 article explores why this happens and how language, cascades and medications magnify the impact.This article is part of our healthcare in workers’ compensation series, exploring how common care practices can unintentionally add to harm and shape outcomes.

Part 1: System use and outcomes

Early spinal imaging is consistently associated with longer disability, more procedures and higher opioid exposure—particularly in workers' compensation.

This has been a challenging topic for us to tackle; we need to present the depth of evidence whilst keeping people at the centre of our focus. We've done our best to present this information in an impactful way—this is a shared problem and addressing it together offers the best opportunity for meaningful improvement.

Michael strained his back lifting equipment at work. An X-ray noted "degenerative changes." An MRI listed "multilevel disc disease." The language felt ominous. He stopped moving "in case it made the damage worse," cycled through specialist appointments, and—while waiting for decisions—started opioids. Six months later, he'd had a dozen studies, higher pain, lower function, and no clearer plan. His scans didn't just fail to help. They nudged his recovery in the wrong direction.

Early imaging isn't neutral. Across randomised trials and cohort studies, it is associated with more persistent pain, longer disability and greater exposure to procedures and opioids—particularly in workers' compensation. Imaging is doing harm.

By the numbers (selected studies)

This pattern is common. Across multiple study designs—randomised trials, cohort studies, and large administrative datasets—and what we see in clinical practice, early or unnecessary spinal imaging is linked with worse pain, longer disability, more invasive procedures, and higher opioid exposure. The mechanism isn't the magnet or the machine. It's what follows: how findings are labelled, how people make sense of them, and how those beliefs steer choices. This is widespread across healthcare and is especially pronounced in workers' compensation.

Further studies examining patient interpretation studies, clinical outcomes, and economic impacts is provided in the appendix. Here are selected studies that are discussed below demonstrating the pattern:

- In a controlled study where patients were told their scan results or kept unaware: 246 patients underwent identical MRI scans and half learned their results while half remained blinded. Those told about their findings experienced declining general health perceptions lasting over a year, while those unaware of identical findings maintained stable health ratings above baseline (1).

- In a randomised controlled trial of 421 people with back pain: participants were randomly divided into two groups—half received lumbar X-rays and half were managed without imaging. Three months later, those who had X-rays were 26% more likely to still have back pain, reported worse overall health, and had poorer physical functioning compared to those who didn't get scans (2).

- In a workers' compensation study following 1,770 injured workers: researchers compared workers who received MRI scans early after their injury with similar workers who didn't get early scans. Those with early imaging were off work for a median of 174 days compared to just 21 days for the no-imaging group—more than eight times longer. The early imaging group also accumulated higher medical costs and reported significantly more psychological distress (3).

- In a large retrospective study of 57,293 patients: those who received early MRI had 12.7 times higher odds of lumbar surgery and were 23% more likely to receive opioid prescriptions compared to those managed without early imaging (4).

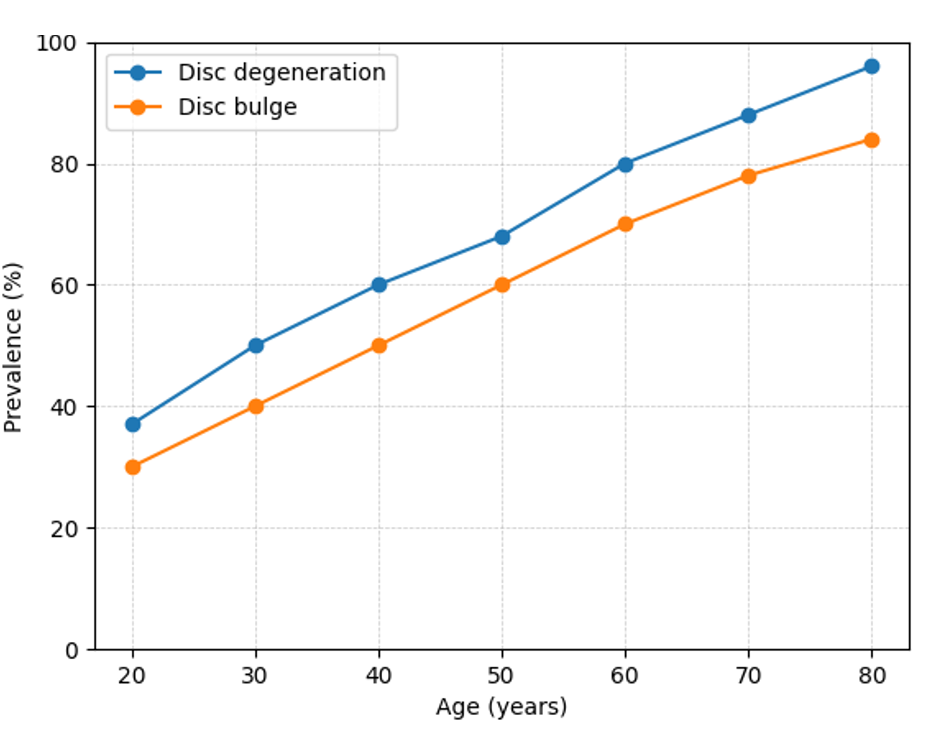

- In a systematic review examining scans from healthy people: researchers found that so-called "abnormalities" like disc degeneration and bulges are extremely common at all ages and increase naturally with age—present in 37% of healthy 20-year-olds and 96% of healthy 80-year-olds who have never had back pain, with the gradual increase in so called degenerative change shown in the chart below (5).

How imaging produces harm

Words wound

Report language shapes beliefs and behaviour. Terms such as "degeneration," "disc bulge," or "degenerative disc disease" sound pathological to lay readers and to many referrers. The same anatomy, described differently, produces different outcomes.

Patient interpretation studies reveal the gap between medical intent and patient understanding. Research shows that people reading their own radiology reports consistently show higher concern levels for common medical terms than spine specialists consider appropriate, with these concerns directly correlating with increased symptom reporting and catastrophic thinking.

The power of words becomes clear when we see what happens to people. In controlled studies, participants who received lumbar X-rays were more likely to report persistent pain months later, with lower health status and function, compared with those managed without imaging. The imaging appeared to "encourage or reinforce the patient's belief that they are unwell". When people were told their MRI results versus being kept unaware of identical findings, those who learned about their scans experienced declining health perceptions that lasted for a year, while those blinded to the same results maintained stable health ratings. The effect isn't anatomy—it's attribution. Being told "you have a disc bulge" becomes "my spine is damaged," which drives fear and avoidance.

Normal findings, harmful meanings

Large systematic reviews in asymptomatic populations show that so-called "abnormalities" are commonplace: disc degeneration in many younger adults and the vast majority of older adults; disc bulges rising steadily with age (5). Without this context, a line like "multilevel degeneration and disc bulges" is easily misread as disease rather than age-typical variation—prompting rest, avoidance, time off work, and a drift toward procedures.

The phrase "grey hairs on the outside, grey hairs on the inside" captures this reality: what we see on scans often reflects normal ageing, not damage requiring intervention.

Cascades amplify exposure and risk

Among injured workers, early MRI has been associated with substantially longer disability duration and higher medical costs, alongside greater psychological distress (3). Large observational studies link early MRI with markedly higher risks of lumbar surgery and opioid prescribing (4). While observational studies cannot definitively establish causation due to potential confounding factors, the consistency of findings across different study designs, populations, and healthcare systems strengthens the evidence that imaging contributes to poorer outcomes.

Early imaging sets off a chain reaction—procedures, prescriptions, appointments—that makes return to function less likely, not more.

What we've known—and what we overlook

Imaging remains essential when results will change management—red flags, progressive neurological deficit, trauma, or surgical planning. We have known for decades that routine imaging for non-specific spinal pain rarely improves outcomes and guidelines advise against it unless there is a specific indication. Yet the standard workflow often persists: order the scan, let the report wording set the narrative and drift away from evidence-based care.

The harms from this operating model are now well documented—prolonged disability, more procedures and medications, and loss of confidence in movement—particularly in workers' compensation. Healthcare's contribution to these problems is often hidden until we examine patient interpretation, delays, cascades and outcomes together.

Why this matters for schemes

We're supposed to be helping people recover and return to their lives. Instead, we're contributing to harm. Behind each statistic—the eight-fold increase in disability duration, the 12-fold increase in surgery risk—are real people whose recovery we've complicated.

These are workers whose straightforward injuries became complex disabilities. People who started with a sore back and ended up identifying as permanently injured. Young apprentices whose careers never recovered from a minor strain because we taught them their spine was damaged. Families under financial stress as weeks off work stretched into months, then years.

When someone with a simple back strain ends up on long-term opioids, avoiding movement, and unable to work—not because their tissue injury was severe, but because of how we investigated and described it—we've failed in our fundamental purpose. Many of these people never fully return to their previous function or work capacity. Some develop chronic pain conditions that persist long after their original injury should have healed. Others become long-term users of the compensation system, cycling through treatments that may have been preventable with different early choices.

The human cost is profound, and it's largely invisible because we track approvals and expenditures more carefully than we track whether people actually get better.

Where this meets language

The harm from imaging extends beyond the decision to scan. How we label and communicate findings shapes recovery trajectories in ways that can compound the initial damage.

In part 2, we examine how diagnostic language and communication failures amplify these imaging harms, turning normal age-related findings into barriers to recovery.

Questions for discussion

- If around half of workers with back claims undergo imaging within two years [4] and if 10–15% of those imaged experience worse outcomes as trials and cohort studies suggest [5][6][7]), what does that mean for each jurisdiction in terms of the number of workers potentially harmed by routine imaging?

- Which imaging approvals demonstrably change management and which add delay without clinical benefit?

- What minimum data should schemes capture on time to first effective treatment and imaging-to-surgery pathways to detect harmful cascades early?

- How would we measure progress—imaging rates by indication, disability duration by early imaging status, procedure rates following imaging—to show we are reducing harm while maintaining appropriate care for genuine indications?

References Part 1

- Ash LM, Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Grooff PN. Effects of diagnostic information on patient outcomes in patients with low back pain and radicular pain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(6):1098-1103.

- Kendrick D, Fielding K, Bentley E, Kerslake R, Miller P, Pringle M. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):400-405.

- Webster BS, Bauer AZ, Choi Y, Cifuentes M, Pransky GS. Iatrogenic consequences of early magnetic resonance imaging in acute, work-related, disabling low back pain. Spine. 2013;38(22):1939-1946.

- Di Donato M, Iles R, Buchbinder R, Xia T, Collie A. Prevalence, predictors and wage replacement duration associated with diagnostic imaging in Australian workers with accepted claims for low back pain: a retrospective cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;32(1):55-63. doi:10.1007/s10926-021-09981-8.

- Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):463-72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0.

- Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Early imaging for acute low back pain: one-year health and disability outcomes among Washington State workers. Spine. 2012;37(18):1617-27. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182541f0d.

- Webster BS, Cifuentes M. Relationship of early magnetic resonance imaging for work-related acute low back pain with disability and medical utilization outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(9):900-7. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181f26f1f

Published 09 September, 2025 | Updated 09 September, 2025