‘This is so unfair’. Preventing perceptions of injustice after a work injury.

Lauren Finestone

A sense of injustice is common among injured workers and can prolong their suffering. What causes it? And how can we prevent it?Injuries at work aren't just physical setbacks. They can cause emotional suffering and have serious consequences for recovery.

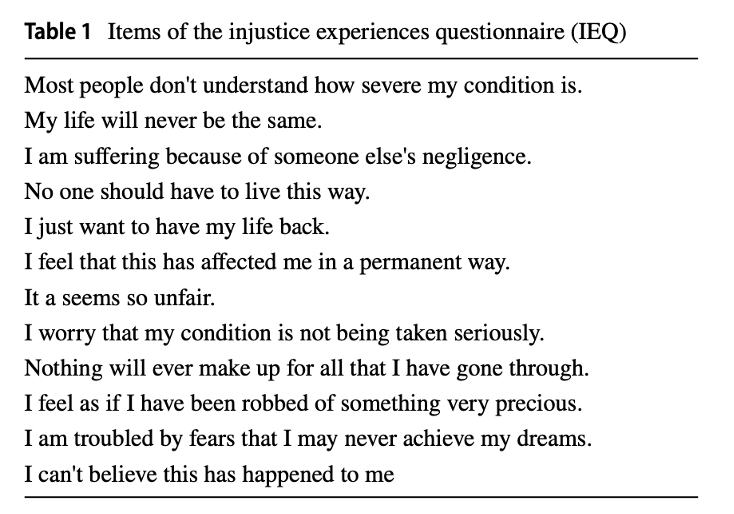

What’s interesting is that a sense of injustice — the feeling that what happened to them was unfair or happened because someone did the wrong thing — is also very common among injured workers.

And this sense of injustice can prolong suffering. It can cause more severe pain, reduce function and result in mental health issues like depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.

To better understand what fuels these feelings of injustice and what interventions might be effective, a study interviewed people who scored high on measures of perceived injustice after a work injury.

It uncovered the common causes of feelings of injustice were invalidation, undeserved suffering and blame.

Invalidation

This was the biggest theme. When an injured worker’s reports of pain, disability or distress are ignored or not taken seriously, it feels unjust.

When they don’t feel heard, understood or believed by their loved ones, employers, doctors and insurers, this lack of validation adds to their stress. If their symptoms or concerns were brushed off they’d be inadequately investigated, treated or compensated.

Validation from loved ones is crucial for emotional and practical support. Validation from health professionals for getting the right medical care and validation from insurers is essential for accessing financial compensation. So without it, people may struggle to receive the support they need to recover fully.

Two types of invalidation

The study identified 2 types of invalidation: lack of understanding and discounting. Discounting causes the most damage because it undermines the legitimacy of their experience and leaves them feeling powerless to access essential support — which only amplifies the sense of injustice.

Pain is invisible

The ‘invisible’ nature of their pain symptoms presents challenges to having their concerns validated. Musculoskeletal problems may have no clear pathological cause despite significant pain, so professionals and non-professionals may doubt the authenticity of their clinical presentation.

Disrespectful communication

People expect to be treated with respect. However, encounters with doctors or insurance representatives often fall short of this expectation. For example, when stigmatising language in reports reveals negative biases towards some patients or health conditions.

The failure to validate the experiences and concerns of people with musculoskeletal pain contributes to feelings of injustice and also undermines their access to appropriate care and support, hindering their journey to recovery.

Undeserved suffering

These workers had a profound sense of injustice as a result of their pain experience. This was because the pain disrupted their valued activities, they anticipated enduring or permanent discomfort and they were aware of the possibility of missed opportunities.

Many saw this as the unfair consequence of some form of miscarriage of justice. Of wrongdoings they hadn't committed.

Blame

Blame was another common thread in workers’ stories. They blamed employers, healthcare professionals and insurers.

Interestingly, blame was often directed at those who had invalidated their experiences, whether through a lack of understanding, acknowledgment or denial of their condition. They especially held employers accountable if they believed their injury could have been prevented.

What types of interventions could be useful?

Individual interventions may not always be appropriate

Some researchers have suggested that approaches like Acceptance and commitment therapy might be useful. However, while this can be helpful for personal coping (like accepting that accidents happen) these strategies might not be as effective or even appropriate when it comes to addressing broader systemic inequalities — like the reality that there are unsafe workplaces and unfair or disrespectful practices by insurers.

Validating communication

Because invalidation was the biggest source of perceived injustice communication would appear to be a promising target for intervention. This would involve people like significant others, healthcare professionals, employers and insurance representatives, which is not without its challenges.

But there are effective ways to promote validating communication:

- Empathy-building interventions have shown promise in improving the validating of pain by patients' partners

- Training employers on how to communicate in a way that validates the worker and the early involvement of employers could be crucial for people with work-related injuries, given that employers were often cited as sources of injustice.

- Training programs like Cognitive Functional Therapy or validation skills training for medical students have also been found to increase the use of validating communication in clinical settings.

Perspective-taking

It might be worth exploring interventions that reduce the likelihood that workers will interpret invalidating communication as injustice.

For example, perceptions of injustice are more common when people see injustice as intentional and avoidable. Injured workers could be given information that explains the challenges loved ones face in understanding ‘invisible’ disabling conditions like musculoskeletal pain.

Similarly, providing information about healthcare practice guidelines followed by healthcare professionals as early as possible after an injury could potentially reduce the likelihood of patients interpreting invalidating communication as injustice.

It may be useful to train insurance representatives to use more respectful language and handle claimants' angry communication without being defensive. But addressing feelings of invalidation when claims are denied is a bigger challenge. Insurers have to assess claims for musculoskeletal conditions, many of which lack objective signs of pathology.

What may help is to encourage the ‘lens’ through which cases are assessed as one of ‘a presumption of genuine disability unless proven otherwise’ rather than a presumption of fraud unless proven otherwise’.

Insurers would benefit from reflecting on where on this spectrum they've positioned their ‘presumptive lens’. This could help ensure fairness and reduce perceptions of injustice.

The takeaway messages

Managing perceived injustice may mean having interventions that address both the injured worker’s perceptions of injustice and actual systemic factors that contribute to people feeling they’ve been treated unfairly.

Original research

Adams, H., MacDonald, J. E., Castillo, A. N., Pavilanis, A., Truchon, M., Achille, M., ... & Sullivan, M. J. (2023). Qualitative Examination of the Experience of Perceived Injustice Following Disabling Occupational Injury. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 1-12.