Flagging the obstacle course of bad outcomes

in 2007, a group of experts in work disability gathered in the UK to celebrate 10 years of the flags concept, and revisited and added to the flags model.

A document: 'Tackling Musculoskeletal Problems - A Guide For Clinic And Workplace' was developed out of this flags ‘think tank’.

One of our heroes, Prof Kim Burton, has kindly sent a hard copy of the document, which can be purchased.

As you might be aware, the flags concept started in New Zealand in the 90s, as a way to ‘flag’ issues and obstacles that impacted on health and return to work outcomes. The flags concept started when three psychologists, reportedly sitting in a hot mud pool in NZ, were talking about how to encourage doctors and others involved with returning people with back pain, to recognise and deal with these issues.

The flags document is a fabulous document that provides a comprehensive coverage of the issues. It provides a useful overview of how to identify obstacles to return to work and how to overcome them.

Our take on the document is that it highlights the contrast between the medical model and actually dealing with what's going on.

The medical model focuses on the medical problem. Under the medical model we might see the following scenario:

Ms X is a 45 year old process worker, who mainly works standing at a bench doing assembly work. She also lifts 10 kg four times a day. She develops back pain one day whilst lifting a 10 kg box. The next day she attends her doctor, who tells her she has a back strain and gives her strong pain tables as she’s complaining a lot.

She is told to rest for a few days and then go back to work on light duties. Her back pain gets worse, so her doctor does a CT scan and she is told this shows she has two disc bulges. Her pain increases, her doctor says to take it easy, and there is some suggestion her job may not be good for her.

At work her supervisor is generally unhelpful, and at home her husband and kids are much the same.

The strong pain tablets don’t help much, so with the next visit to the doctor her description of the pain leads her doc to give her stronger medication and arrange referral to a specialist. Physiotherapy is organised, and the physiotherapist starts giving her heat treatment, ultrasound and mass charge of the back. The physiotherapist tells her it's going to take some time for the treatment to work. The neurosurgeon’s appointment is booked, but it is going to take three months to see him.

Her doctor writes a certificate to say she can return to work on reduced hours, not doing lifting and pushing, pulling or twisting. Her supervisor looks at the certificate and tells her there is little in the way of work that can be done with those restrictions, but finds something to keep her going. The supervisor is less than pleased.

Someone tells her she should have an MRI scan but her doctor tells her it can’t be done until she sees the specialist. Her neighbour tells her the discs in her back might be degenerate.

Ms X goes back to work four hours a day three days a week, but her pain gets worse with the standing, so her doctor puts off work. Her back pain isn't responding to treatment, and she feels she can't do even basic jobs at work. Things at home are going downhill and she is starting to feel awfully negative about what's going to happen in the next 6 to 12 months on, wondering whether she is ever going to recover from a back problem.

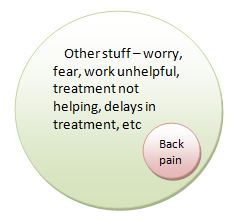

The medical model sees her problem as a back problem. It focuses on investigations and treatment. It's about the presenting issue, without much thought or discussion about the important surrounding issues.

Of course a back problem is important. But treating the back problem isn't really the answer.

Much of Ms X's problem is her worry about the condition. She doesn't understand the basics of back problems, she is not being accommodated at work, and she is suffering from an over medicalisation of her condition which is at best counter-productive and probably harmful

The flags model says, "what's going on here?"

It identifies the problems that are surrounding the back pain, eg negative expectations of recovery, lots of worry and distress and uncertainty.

It recognises there is probably going to be fear of ongoing problems, and worry about reinjury with further lifting. That there may be low job satisfaction and low workplace support. It recognises Mrs X may be worried about her financial future, and that family members and others may be impacting the situation. It recognises Mrs X's confidence may also be having a major impact on the overall situation.

These issues are not difficult to tackle: a decent understanding of the back problem, assurance that the problem is going to get better, and some sensible discussions about appropriate work duties and a plan to return to work are likely to prevent a long-term problem.

The above aren’t generally difficult things to achieve, but if the issues are not identified and dealt with Mrs X may well be off work to 6 or 12 months, and is a real possibility she’ll be off work forever.

The medical model just doesn't cut it. Yet time and time over, we follow it.

The central document to so much of return to work is the medical certificate. The medical certificate quietly but powerfully promotes and maintains the medical model.

Maybe we should have a flags certificate.

Published 26 June, 2010 | Updated 11 February, 2014