Developing a successful rehabilitation program: case study

Dr Garry Pearce, as a rehabilitation physician, was the past president of the Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine and the Director of Health Services at Concord Hospital in NSW.

Garry talks about the rehabilitation program they developed for staff at Concord Hospital and their subsequent research evaluation. This research was conducted with Andrew McGarity as the Rehabilitation Coordinator at Concord Hospital; Darren Wilson, psychologist; A/Prof Michael Nicholas, Clinical Psychologist; and Prof Steven Linton.

MW: Garry, what started you on the path of return to work program development?

"Back in 2004 we had a large number of claims– about 300 open claims. We thought we were providing good quality medical management and case management, but we didn't seem to be making headway in improving our not so good return to work and claim results.

"I had a few particularly difficult patients with chronic pain at the time. This, and the large number of claims and higher-than-average time off work, led us to do reconsider the way we were managing our work injuries.

OK, I get the picture. It’s a difficult situation, and often made more difficult when you are trying to change it from within. What did you do?

"Our initial change in approach was to require employees to attend the staff health clinic for a preliminary assessment. We developed a job bank of suitable duties, met with managers to review and discuss cases, and involved managers more in the rehabilitation program. However these initiatives did not result in a significant improvement in outcomes.

"We did some further soul-searching. Looking at the evidence available at the time we decided we needed to identify people at high risk of long-term time off work and chronic pain as early as possible.

"The concept of yellow flags - or psychosocial factors - was being discussed more and more at the time. Factors such as the person's beliefs about their condition, ‘catastrophising’ (seeing the whole situation as something dreadful) and fear and anxiety, had been found to increase the likelihood of long-term disability.

"WorkCover New South Wales was using the Orebro questionnaire at six weeks to help case managers identify difficult cases. We wanted to use a questionnaire that could be completed within 10 minutes and done in all cases within a few days of the injury.

"So we worked with Dr Michael Nicholas and Dr Steven Linton, two psychologists with expertise in this area, to shorten and modify the Orebro questionnaire.

Did you find the questionnaire of value?

"We piloted the questionnaire with 30 consecutive injured workers. We grouped workers under ‘low risk’, ‘medium risk’ and ‘high risk’ based on the scoring of the questionnaire.

"At about one year post-injury we reviewed this group. We found the average cost of a low risk case was approximately $4 800, medium risk $6 200, and a high risk $17 000. This helped us be comfortable that we were on the right track.

That is pretty solid evidence of the questionnaire being useful. Did you use the results of the questionnaire in determining injury management?

"To help people who may have had psychosocial factors influencing their return to work, we engaged quality providers.

"We had an excellent return to work coordinator on site - Andrew McGarity. We engaged a psychologist experienced in short-term interventions, i.e. helping people within a relatively small number of consultations. We also engaged a selected group of occupational physicians and rehabilitation providers.

"Our intervention approach was as follows:

High Risk (questionnaire score >85)

- Independent Rehabilitation Provider within 2 weeks;

- Independent psychological assessment and treatment within 2 weeks at Staff Health;

- Independent Medical Consultation within 2 – 4 weeks;

- Independent Physiotherapy Assessment after 6 weeks; and

- File review by Medical Director if not returned to work within 4 weeks.

Medium risk (questionnaire score 70 – 84)

- Psychologist assessment and treatment within 2 weeks of injury plus ‘usual care’; and

- Independent Medical Consultation within 1 month.

Low risk (questionnaire score <69)

- ‘Usual care’.

And you found...?

"Our study followed a group of 80 workers with an injury who had ‘usual care‘. That means they still attended our clinic, had usual management of their medical injury and had usual return to work management approaches. This was the control group.

"Our trial group of another 80 workers with an injury had the specifically designed intervention. The intervention they received was determined by their questionnaire score, and is as listed above.

"Those designated to be medium risk were seen by the psychologist, and had an independent medical assessment at one month.

"Those in the high risk group had a psychological assessment, an independent medical review, and an external rehabilitation provider was assigned to assist return to work, etc.

"There was not a significant difference in the results between the control and intervention groups for the low and medium risk groups.

"However, we found a significant difference in outcomes and costs for high risk group. In the control group, costs were approximately $17,000 on average and in the intervention group the costs were just under $13,000.

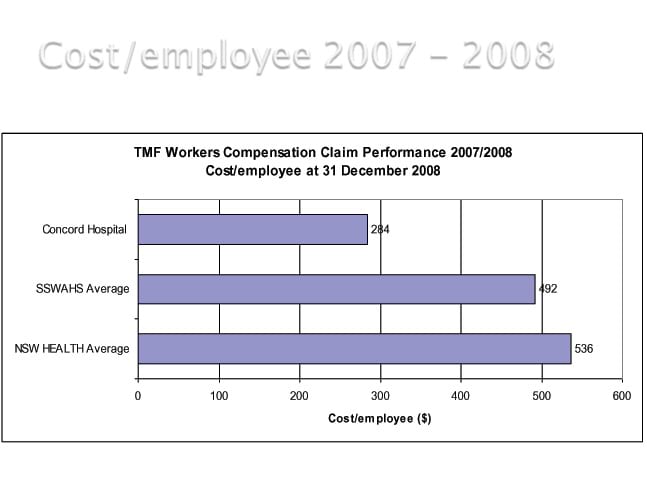

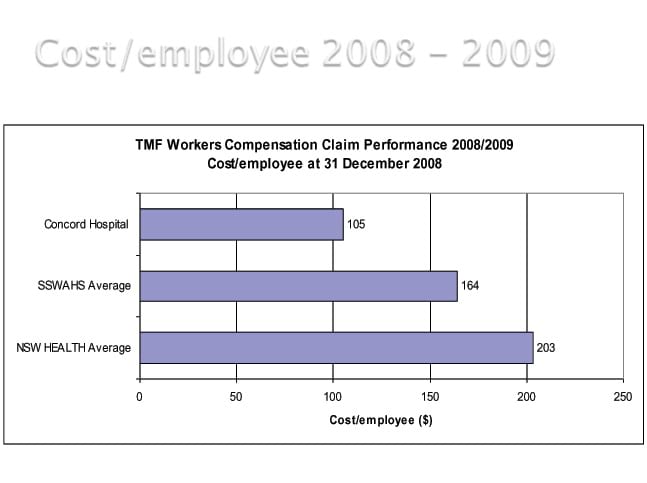

"We also had a reduction in cost per employee and this has continued to drop over the last six years. In the graph you can see the drop in cost at Concord compared to the area health service and NSW Health we operate within.

What do you think were the key differences that resulted in improvement in the high risk cases?

"Our work says there are no quick fixes, but a longer term strategic approach can make a big difference.

"I think the key elements of our approach were consistent staff, people who cared about providing a good service and achieving outcomes, and executive/ CEO buy-in.

"Leadership in managing return to work was important and having the right people working together as a team paid off. Once the program was working well, the system ensured that those at high risk of disability within the workers compensation system were picked up early and managed accordingly.

"Having a psychologist involved was a very positive strategy. We approached people in a sensitive manner about seeing a psychologist, offering them the option and explaining how a psychologist may assist them. We had very few people not accepting the offer of attending the psychologist.

"Consulting all relevant stakeholders as the program was set up paid off. It takes extra time, but if you have people involved and engaged it is worth it in the long run.

We heard you are planning a larger study...

"While the results of the evaluation we did are positive, it's important to ensure they are reproducible with a full evidence-based study design.

"WorkCover New South Wales, and Employers Mutual Limited, the Treasury Managed Fund insurer, want to support us with further funding. A randomised control trial - where people are randomly assigned to the treatment or control group - is now being set up. While I now live and work in Tasmania, I’ll still be involved with the study from a distance.

"It's interesting that even though work injury management is a major problem in Australia - both in terms of the health impact on people and the cost to the community - there’s little practical research in this area. We hope the larger study that is going to be undertaken will help provide evidence of what works, for other people who work in the field.

"Of interest, we did not have any patients in the intervention group that went on to develop chronic pain type problems. Chronic pain is a major problem in terms of health outcomes, long-term disability and health consequences for the individual. It is also a tough problem for the practitioners involved in the person's care. If we can significantly reduce the level of chronic pain, it will make a difference to the health and well-being of people in Australia and to their workplaces.

Published 22 May, 2011 | Updated 06 November, 2013